- PMID: 15061633

- PMCID: PMC387439

Free PMC article

Abstract

We report a case of congenital absence of the anterior pericardium in a 41-year-old man who was undergoing implantation of a left ventricular assist device for treatment of congestive heart failure.

Keywords: Cardiomegaly, heart failure, congestive, heart assist devices, heart defects, congenital, pericardium/abnormalities, ventricular remodeling

Congenital absence of the pericardium (CAP) is rare. 1 The published world medical literature regarding this condition contains few cases of right-sided defects or complete defects and is dominated by reports of left-sided defects arising from agenesis of embryologic precursors. 1–4 We found no reports of anterior pericardial defects. When CAP is associated with underlying heart disease, diagnosis with conventional imaging techniques may be more difficult and treatment more problematic. Herein, we report a case of a large anterior CAP in a patient who was undergoing implantation of a left ventricular assist device (LVAD) for treatment of congestive heart failure (CHF).

Case Report

A 41-year-old man with a history of CHF and hypertension presented at a regional hospital with worsening symptoms of dyspnea, orthopnea, and paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea. He was referred to our institution for treatment in October 2001.

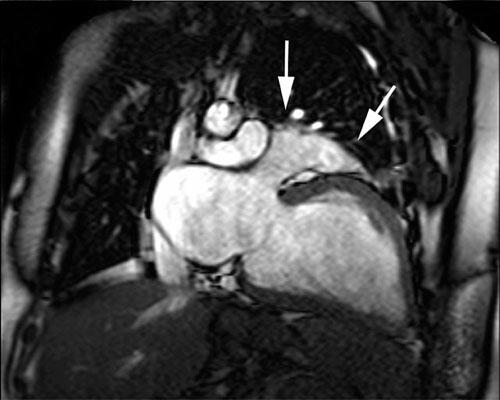

Physical examination revealed an increased jugular venous pulse, diffuse rhonchi at both lung bases, and peripheral edema. Chest radiography showed no abnormalities of the mediastinum; however, the cardiac silhouette was enlarged, and there was mildly increased pulmonary vascularity without pleural effusion. Electrocardiography revealed normal sinus rhythm, right-axis deviation, and incomplete right bundle branch block. Echocardiography showed severe left ventricular dysfunction with global dyskinesia, an ejection fraction of 0.10, and mild mitral and tricuspid valve insufficiency. All 4 cardiac chambers were dilated, but there was no wall thickening. Coronary angiography revealed normal coronary arteries. Ventilation/ perfusion scanning showed no pulmonary embolus. Cine magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) (Figs. 1 and and2)2) revealed marked dilatation of all 4 cardiac chambers, displacement of the heart so that it occupied most of the lower left half of the left hemithorax, displacement of the cardiac apex posteriorly within the left hemithorax, and tortuous pulmonary arteries.

While the patient was hospitalized, his condition deteriorated to the point that implantation of an LVAD was required. A midline sternotomy was performed, revealing an absence of anterior pericardium with myocardial bridges present posteriorly and laterally. A left ventricular reduction procedure was performed, during which a 4- × 3-cm wedge of myocardium was resected. The redundant mitral leaflet was repaired with an Alfieri stitch on the posteromedial commissure. An LVAD (HeartMate® VE, Thoratec Corp.; Pleasanton, Calif) was placed intraperitoneally, with its inflow cannula inserted into the left ventricular apex and its outflow graft anastomosed to the ascending aorta. No attempt was made to repair the pericardial defect. The patient’s postoperative recovery was satisfactory. Histologic analysis of tissue removed from the left ventricular apex during cannula insertion showed myocyte hypertrophy with focal areas of scarring, which was consistent with cardiomyopathy.

Discussion

The present case includes the extremely rare finding of anterior CAP and an abnormally large heart as seen preoperatively on MRI and intraoperatively. Both the preoperative MRI findings and the intraoperative findings raised the question of whether there was any association between the patient’s cardiomyopathy and the loss of the structural support and stabilization that an intact pericardium would have provided.

Congenital absence of the pericardium is a rare but well documented clinical phenomenon. 1 It represents not a single entity but a spectrum of abnormalities ranging from very small pericardial defects to complete agenesis occurring as a result of perturbations in the development of the common cardinal veins during embryogenesis. Normally, the left common cardinal vein develops into the left pleuropericardial membrane, and the right common cardinal vein forms the superior vena cava with concomitant closure of the right pleuropericardial membrane. Congenital pericardial defects can occur alone or in association with other congenital anomalies. 2 Reports of right-sided pericardial defects in the literature are few, but some of them suggest that the superior vena cava may persist on the left side but be absent on the right. 5

Patients who have CAP may show no symptoms, mild symptoms, or intractable symptoms requiring surgery. 1 In asymptomatic patients, CAP is usually diagnosed incidentally on a chest radiograph performed for other reasons. Symptomatic patients often describe a sharp, stabbing, left-sided chest pain that may be postural. 6 Although its cause is unclear, the pain may be due to tension on pleuropericardial adhesions in the presence of partial defects.

With or without symptoms, CAP is often difficult to diagnose. However, certain characteristic features can be identified by various imaging techniques. On the chest radiograph, left-sided CAP is often indicated by a cardiac silhouette that is displaced to the left with a right heart border that is lost to view by superimposition of the vertebral column. A “tongue” of lung tissue may also be seen between the pulmonary artery and the aorta. 1 Frequently, however, the chest radiograph is not diagnostic. Echocardiography may rule out other structural defects. It may also allow visualization of paradoxical ventricular septal motion and other subtle findings, such as bulging of the inferior left ventricular wall during diastole. 7 Computed tomography 8 and MRI 9 are especially useful. Both techniques can reveal levoposition of the heart, interposition of lung tissue between the inferior aspect of the heart and the diaphragm, and abnormal extension of the main pulmonary artery and the left atrial appendage beyond the margins of the mediastinum.

In our patient, the diagnosis of CAP was confounded by the abnormally dilated cardiac chambers seen on cine MRIs. Although the displaced apex and enlarged left atrial appendage may have prompted us to consider a diagnosis of CAP, they did not enable us to make a definitive diagnosis until surgery, since the chamber dilatation could also have caused the distortion and malposition of nearby anatomic structures visible on the chest radiograph.

Because CAP is rare and most of the published literature consists of case reports, treatment options are unclear. In asymptomatic patients, observation alone is adequate. However, because the heart and great vessels tend to move within the mediastinum, some clinicians have advocated repair in such cases, if thoracotomy is being performed for other reasons. 3 When symptoms are debilitating or if the atrial appendage has herniated through a pericardial defect, corrective procedures, such as left atrial appendectomy, pericardioplasty, or extension of the pericardial defect, might also be beneficial. 1 The presence of cardiomyopathy in our patient suggests that some benefit might also be gained by earlier diagnosis and treatment with innovative—although as yet unproven—techniques such as passive containment with a cardiac support device. 10,11

Herein, we describe the case of a patient with symptoms of congestive heart failure in whom congenital absence of the pericardium was confirmed during surgical implantation of a left ventricular assist device. No attempt was made to repair the large defect during surgery, because it was assumed, correctly, that the left ventricular assist device would adequately stabilize the heart.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: Gregory N. Messner, DO, Texas Heart Institute, MC 2-114A, P.O. Box 20345, Houston, TX 77225-0345

E-mail: ten.epacsten@gergssem

References

Congenital absence of anterior pericardium is a rare congenital condition in which the anterior part of the pericardium, the protective sac surrounding the heart, is absent or underdeveloped. This absence can leave the heart more exposed to injury or complications, as the pericardium normally provides a protective layer and maintains the heart’s position within the chest. The condition is typically diagnosed incidentally during imaging studies conducted for other reasons, as many individuals with this anomaly do not present symptoms.

In cases of congenital absence of anterior pericardium, the heart may be more prone to displacement, and in some rare instances, it may cause the heart to shift in the chest cavity. While the condition itself may not always lead to significant health issues, it can increase the risk of certain cardiovascular problems such as pericardial effusion, which occurs when fluid accumulates around the heart. Additionally, the absence of the anterior pericardium may leave the heart vulnerable to external trauma, as there is less protection surrounding the organ.

Patients with congenital absence of anterior pericardium are often monitored for any complications that may arise. In some cases, surgical intervention may be required to either reconstruct the missing pericardial tissue or to manage complications like fluid buildup or abnormal heart positioning. While many people with this condition lead normal lives, careful management and regular check-ups are important to detect potential complications early.

Overall, congenital absence of anterior pericardium is a rare and often asymptomatic condition that requires specialized care to prevent or address any heart-related issues that may emerge. Early diagnosis and careful monitoring can help ensure that individuals with this anomaly can live healthy lives despite the structural difference in their hearts.