- PMID: 15061635

- PMCID: PMC387441

Abstract

Malignant tumors that metastasize to the heart pose a formidable therapeutic challenge. Recent advances in surgical treatment have improved the management and prognosis of patients with cardiac metastases. We report the case of a 45-year-old man who had a high-grade pleomorphic sarcoma of the right ventricle. We completely resected the neoplasm, reconstructed the right ventricle, and replaced the mitral valve. Upon late follow-up, 67 months (5.6 years) later, the patient was alive and well. This case shows that aggressive surgical management of malignant disease metastatic to the heart can enable prolonged survival.

Keywords: Cardiac metastases, neoplasm, heart ventricle, sarcoma

Nearly a half century after Crafoord 1 accomplished the 1st successful resection of a cardiac tumor using cardiopulmonary bypass, surgical intervention is frequently used to manage patients with cardiac tumors. Techniques for excising cardiac tumors constitute a growing body of medical literature. The preferred technique varies, depending on the location and characteristics of the tumor, but may include palliative resection, complete resection with ventricular reconstruction, 2 or heart transplantation. 3,4

Primary cardiac tumors are observed in 0.0017% to 0.03% of unselected patients at autopsy. 5,6 From 10% to 25% of these tumors are malignant. 1,7 Secondary cardiac tumors are 20 to 40 times more common than are primary ones. 8 Although 10% to 25% of patients with terminal cancer have cardiac metastases, 9,10 clinical evidence is scarce, and premortem diagnosis is unpredictable.

We report a case of sarcoma metastatic to the right ventricle that was treated by means of aggressive surgical intervention. We detail our surgical technique, review the current English medical literature on surgical intervention for cardiac neoplasms, and emphasize the importance of an aggressive surgical approach.

Case Report

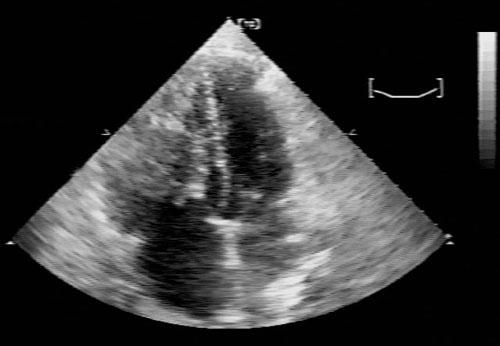

In July 1997, a 45-year-old man presented at our institution with dyspnea, fatigue, and diminishing exercise tolerance, which had begun a month before admission. Twenty-seven months earlier, a biphasic sarcoma had been excised from the patient’s left axilla. At the present admission, physical examination revealed a new murmur, and echocardiography showed a right ventricular tumor. Computed tomography revealed an irregular, nonhomogeneous right ventricular mass, which occupied most of the ventricle and extended to the right ventricular outflow tract (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1 Echocardiography, 4-chamber view, shows a large, heterogeneous, echo-dense mass that occupies the entire right ventricular cavity. The mass extends at least to the pulmonary valve level, causing subtotal obliteration of the right ventricular outflow tract. The lesion involves the tricuspid papillary muscle and chordal apparatus; during systole, small fronds prolapse across the tricuspid valve into the right atrium.

Surgical Procedure

At surgery, a median sternotomy, followed by a right ventriculotomy, revealed a large ventricular mass that originated from the anterior right ventricular wall and extended to involve the chordae tendineae and the papillary muscles to the tricuspid valve. Through the right ventriculotomy, we resected the portion of the anterior right ventricular wall that had been invaded by the tumor; we then resected the involved chordae and papillary muscles through a right atriotomy. Next, we resected the entire tumor and saw no gross evidence of residual disease. After reconstructing the right ventricle with a Teflon-pledgeted 2-0 polypropylene running suture, we excised the anterior tricuspid valve leaflets through the atriotomy, leaving the posterior leaflet in place. We then implanted a 31-mm Carbomedics® mitral valve (Sulzer Carbomedics Inc.; Austin, Tex) and closed the atriotomy. Postoperative transesophageal echocardiography showed no evidence of residual intracavitary tumor.

On histologic examination, the mass measured 14 × 11.5 × 4 cm and weighed 184.6 g. The pathologic diagnosis was high-grade pleomorphic sarcoma (consistent with the previously excised biphasic axillary tumor).

The patient was extubated less than 24 hours postoperatively. He recovered without complications and was discharged from the hospital 10 days postoperatively. At 67 months (5.6 years), a follow-up examination revealed no gross abnormalities.

Discussion

Although cardiac metastases were first described in 1700, 11 the 1st surgical intervention for this rare condition was not performed until the early 1950s. 1 Since that time, advances in surgical technology and technique, along with a growing body of experience, have improved the prognosis for patients with cardiac metastases. Although surgical treatment of benign cardiac tumors is often curative, malignant tumors— particularly those that are metastatic—present a difficult clinical challenge. In certain cases involving extreme regional extension or widespread metastases, the role of surgical intervention is to establish a premortem diagnosis as a guide to adjuvant therapy. 7 The operative risk and the extent of widespread disease must be carefully weighed against the expected benefits. Complete surgical resection is indicated for patients with a preoperative Karnofsky performance status of >80%, 12 minimal extracardiac disease, or a deteriorating clinical condition related to cardiac symptoms. Centofanti and co-authors 13 advocate wide resection of primary malignant cardiac tumors to allow definitive histologic diagnosis and to relieve mechanical obstruction; their strategy has its basis in reports of prolonged survival after extensive resection. In patients with malignant or metastatic disease, palliation and even cure are possible with aggressive surgical intervention. 14 This approach can provide significant benefits and should not be withheld because the disease is seemingly incurable. 7

Various techniques can be used to excise malignant cardiac tumors, depending on the characteristics and location of the tumor, and the overall extent of the disease. These techniques include en bloc excision, subendocardial dissection of the tumor from its base, or en bloc excision of the tumor with a full thick-ness of septum, followed by closure with a Dacron patch. 15 Cooley 15 described a case in which cardiac explantation and autotransplantation were necessary to adequately visualize and excise an extensive paraganglioma. Goldstein and co-authors 4 described 6 cases in which cardiectomy resulted in surgical margins free of the tumor; orthotopic heart transplantation permitted long-term survival without tumor recurrence. Talbot’s group 3 performed heart and lung transplantation for unresectable primary cardiac sarcoma in 4 patients whose median postoperative survival time was 31 months. Chachques and coworkers 2 proposed that complete surgical resection, followed by ventricular reconstruction, is superior to cardiac transplantation in patients with large ventricular tumors. Their 4-step approach consisted of tumor resection, coronary artery resection if necessary, valvular reconstruction, and ventricular wall reconstruction. This approach is similar to the one used for our patient.

A diagnosis of cardiac neoplasm, especially metastatic disease, carries a poor prognosis. Kamiya and colleagues 16 reviewed the cases of 135 patients (in multiple series) who had malignant cardiac tumors; only 3 patients remained alive 3 years after surgery. Most of them died within 12 months postoperatively. Poole and co-authors 7 summarized all the cases in the medical literature that involved primary and secondary malignant tumors of the heart for which surgery was the primary treatment. Patients with primary cardiac neoplasms who survived surgical treatment had a mean survival of 14 months and a median survival of 8.5 months (range, 2–55 months).

Secondary tumors are far more common than primary tumors of the heart; nonetheless, operative intervention is less often undertaken to treat secondary tumors. Poole and associates 7 reviewed 10 cases involving surgically resected metastatic cardiac tumors: the perioperative mortality was 40%; the mean survival time was 12.6 months; and 3 patients remained alive at 7, 9, and 15 months. Murphy and colleagues 14 surgically treated 19 patients who had cardiac metastases. Seventeen patients survived the operation, but there were 4 early deaths. Of the 13 patients who were discharged from the hospital, 8 died an average of 4.2 months after the operation, and 5 were alive after an average follow-up of 3.2 years. Ravikumar and co-authors 11 reported the resection of a metastatic liposarcoma and summarized 10 case reports of successful removal of cardiac metastases. Long-term follow-up was not mentioned in all the reports, but 5 patients with metastatic sarcoma survived for 4 months or more (the longest survival period was 2 years). These investigators noted a trend toward prolonged survival after resection of the cardiac tumor if the interval between primary surgery and recurrence was long.

Although careful patient selection is important, aggressive surgical intervention is clearly of benefit to patients with metastatic cardiac disease. Our case confirms that surgery can be an effective therapeutic choice for these patients.

Acknowledgment

We thank Antonieta I. Hernandez, MD, Senior Analyst in Echocardiography at St. Luke’s Episcopal Hospital/Texas Heart Institute, for interpreting the echocardiogram.

Footnotes

Address for reprints: O.H. Frazier, MD, Texas Heart Institute, MC 3-147, P.O. Box 20345, Houston, TX 77225-0345

E-mail: ude.cmt.iht.traeh@reizarFO

References

Articles from Texas Heart Institute Journal are provided here courtesy of Texas Heart Institute

Sarcoma metastatic to the right ventricle is a rare but serious medical condition in which sarcoma, a type of cancer originating in soft tissues, spreads to the heart, specifically the right ventricle. This metastatic spread is uncommon, as most cancers tend to affect other organs before reaching the heart. When cancer metastasizes to the right ventricle, it can lead to severe complications, including heart failure, arrhythmias, and impaired circulation.

The symptoms of sarcoma metastatic to the right ventricle can vary depending on the extent of the cancer’s spread, but they often include shortness of breath, fatigue, chest pain, and swelling in the legs. Because these symptoms overlap with those of other cardiac conditions, the diagnosis of metastatic sarcoma may be delayed. Advanced imaging techniques, such as echocardiography, CT scans, or MRI, are essential for identifying the presence of tumors within the heart.

Treatment of sarcoma metastatic to the right ventricle typically involves a combination of surgical intervention, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy. Surgery may be necessary to remove the tumor, but this depends on the size and location of the metastasis, as well as the overall health of the patient. Chemotherapy and radiation are often used to target the cancer cells and reduce the likelihood of further spread. Unfortunately, the prognosis for patients with metastatic sarcoma involving the right ventricle is often poor, and the condition requires timely and aggressive treatment to improve outcomes.

Due to the rarity of sarcoma metastatic to the right ventricle, it is important for patients to be under the care of a specialized medical team. Early detection and appropriate management can help alleviate symptoms and may improve the patient’s quality of life.